Those of us in the Great Lakes region (and the rest of the US and Canada) live in a so-called “throw-away society” in which consumerism is rampant, and goods are not often designed or produced with durability in mind. In fact, in recent years, more and more goods are designed to be explicitly or implicitly disposable. Even complex products, such as consumer electronics, are treated as if they are meant to be ephemeral. The classic example is the smartphone. These devices are astounding feats of scientific innovation and engineering. For perspective, consider ZME Science’s article from September 2017: Your smartphone is millions of times more powerful than all of NASA’s combined computing in 1969. Despite their complexity, and the fact that you, and probably everyone you know, barely scratch the surface in terms of using these devices to their full potential, we are constantly bombarded with cues to upgrade to the latest model. And new models seem to be released ever more frequently, always being touted as somehow greatly more advanced than their predecessors. A simpler example is clothing–when was the last time you sewed up or patched a hole in a shirt or pair of pants? Something that once would have been done by most people as a matter of course might now be deemed peculiar. A modern member of our culture might wonder why one would bother to patch a pair of pants when a new pair could be obtained so cheaply.

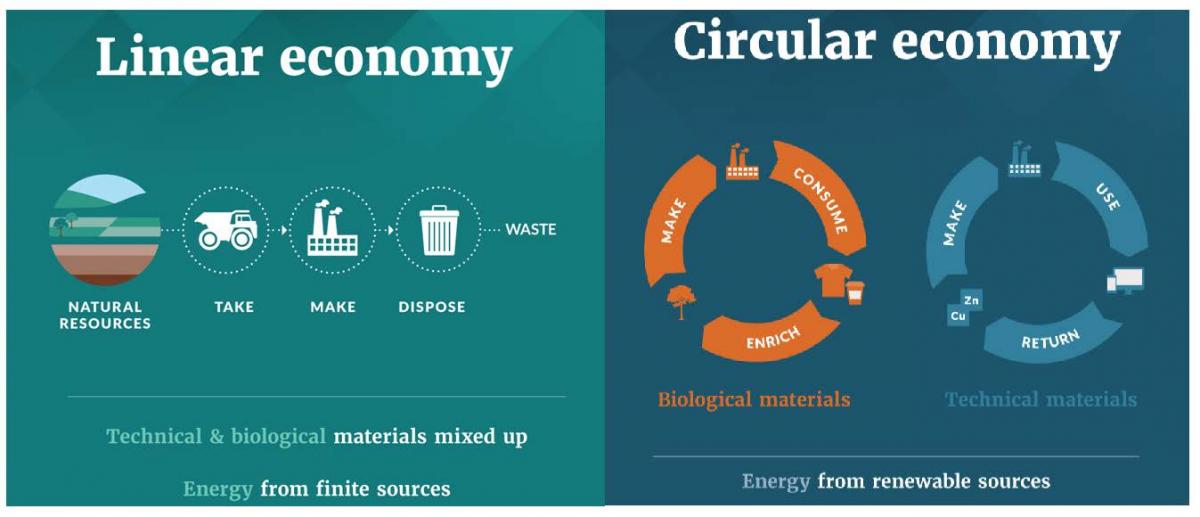

Our “take-make-dispose” model can also be called a linear economy, and the message you receive in such a system is clear: if you have something that becomes damaged or has minor performance issues, you should just replace it. In fact, even if what you have is working well, the time will quickly come when you should just replace the old with the new. Replace, rinse, and repeat. A linear economy is one in which natural resources are extracted and used to create goods which will entirely, or partially, inevitably end up in landfills or incinerators. Some materials may be recovered and recycled, but over time these materials degrade in quality and are used for increasingly lower grade purposes, so that ultimately they will become waste, of little or no further use.

Of course, in order to replace whatever is being disposed of, new goods are required. And those new goods require as much or more resources as the ones that went before them–new minerals and other raw materials must be extracted. Extraction processes can have negative environmental and social impacts (e.g. pollution, habitat destruction, human rights issues related to labor practices, health issues related to exposure to chemicals or physical risks, etc.). Materials are transported to factories (requiring the use of energy in the form of fuel) where they are transformed into new products, again potentially with new human exposures to toxins or other adverse conditions, and potential new emissions of toxins or other substances of concern. In the case of products such as electronics, sometimes components are manufactured in places distant from each other and must be further transported to be brought together in yet another factory to create a complete device. And the finished product is in turn transported across the globe to reach consumers, resulting in more expenditure of energy, more emissions. By the time most products reach the consumer, a great deal of natural and human resources have been invested in them, and however positively the product itself may impact a human life or the broader ecosystem, the number of potential negative impacts all along the supply chain have stacked up. Clearly, any tendency to treat products as disposable, purposefully or incidentally, exacerbates those negative impacts by requiring the manufacture of more products, more quickly than might otherwise have been the case, as long as the demand for product does not diminish.

The tragedy of this linear cycle of use and disposal has lead to the advocacy for a circular economy–one in which extraction of resources is minimized and products and services are designed in such a way as to maximize the flow of materials through resource loops as close to perpetually as physically possible. In such a system, what might have once been considered “waste” continues to be valued in some form or another. A circular economy is built upon design for durability, reuse, and the ability to keep products in service for as long as possible, followed by the ability to effectively reclaim, reuse and recycle materials.

So while the industrial designers of tomorrow will hopefully create products that are in line with the more circular worldview, what can you as a consumer do today to foster a circular economy? Of course you can reduce your use of materials, but practically, you will still need to use some products in order to support yourself, your family, and your lifestyle. You can reuse materials for something other than their original purpose, and sell or donate unwanted functional items so that someone else may use them. Similarly you can purchase items that have been previously used by someone else. And recycling of materials after the end of their original purpose allows for at least some extension of their value. But there is another “r,” which in some ways can be seen as a specialized form of reuse, that is becoming more popular–repair. If you own something with minor damage or performance issues, you can choose to repair it rather than replace it. According to WRAP, a UK organization dedicated to resource efficiency and the circular economy, “Worth over £200m in gross revenue each year, 23% of the 348,000 tonnes of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) collected at household waste and recycling centres could be re-used with minor repairs.” The US company iFixit reports similar statistics, and further states that for every 1000 tons of electronics, landfilling creates less than one job, recycling creates 15 jobs, and repair creates 200 jobs.

There are many barriers to repair, including costs (real or perceived), knowledge, confidence in those performing the repair (one’s self or someone else), and access to tools, instruction manuals and repair code meanings which tell technicians exactly what the problem is so they can address it. Manufacturers of a variety of products, particular those with electronic components (everything from automobiles to cell phones to tractors) have come under pressure in recent years over the attempt to monopolize access to parts, tools, and necessary information for performing repairs, leading to what is called the Right to Repair movement. Currently, 18 US states, including Illinois, Minnesota, and New York in the Great Lakes region, have introduced “fair repair” bills which would require manufacturers of various products to make those tools, parts, and pieces of information accessible to consumer and third-party repair shops. You can read more about the history of the right to repair movement and right to repair legislation on the Repair Association web site.

In an increasing number of communities around the world, citizens are coming together to share their knowledge, tools, and problem-solving skills to help each other repair every day items for free. I’m writing this on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and here are some examples of local projects that can help you repair the items you own:

- Illini Gadget Garage. This one’s my favorite, but I’m admittedly biased, since I helped launch this project and coordinated it for the past few years. The IGG is a collaborative repair center for personally-owned electronic devices and small appliances. “Collaborative repair” means that project staff and volunteers don’t repair your device for you; rather they work with you to troubleshoot and repair your device. Assistance is free; consumers are responsible for purchasing their own parts if needed, though staff can help determine what parts might be necessary. In addition to working with consumers by appointment at their campus workshop, the IGG crew conduct “pop-up” repair clinics in various public spaces around the Champaign-Urbana

community and across campus. Consumers not only benefit from the “do-it-together” approach, they also get access to specialized tools (e.g. soldering irons, pentalobe screwdrivers, heat guns, etc.) that enable device repair, which many folks wouldn’t have in their tool box at home. Though successful repair obviously can’t be guaranteed, project staff say that if it has a plug or electrical component, and you can carry into the shop (or pop-up), they’ll help you try to figure out and fix the problem.

community and across campus. Consumers not only benefit from the “do-it-together” approach, they also get access to specialized tools (e.g. soldering irons, pentalobe screwdrivers, heat guns, etc.) that enable device repair, which many folks wouldn’t have in their tool box at home. Though successful repair obviously can’t be guaranteed, project staff say that if it has a plug or electrical component, and you can carry into the shop (or pop-up), they’ll help you try to figure out and fix the problem. - The Bike Project of Urbana-Champaign. Including both a downtown Urbana shop and a Campus Bike Center, this project provides tools and space for bicyclists to share knowledge and repair bicycles. This project sells refurbished bikes, and individuals who are willing to work on fixing up a donated bike (with assistance) can eventually purchase a bike at a discount. See https://thebikeproject.org/get-involved/join-the-bike-project/ for membership fees; an equity membership based on volunteer hours is available.

- CU Community Fab Lab. Though technically a makerspace, this project provides access to a variety of tools that individuals may not own themselves, as well as a community of tinkerers and creative minds to foster sharing of knowledge. See http://cucfablab.org/inside-the-lab/tools/ for available tools. Note that some fees may apply for consumable materials. Workshops are also offered to help you learn various skills. The Fab Lab is free to anyone in the community during open hours.

- Makerspace Urbana. Another local makerspace, which like the Fab Lab, provides access to tools and expertise of fellow space users. Anyone can use the space for free during open hours; members who pay a fee can obtain a key for 24/7 access. See their list of available tools. They also offer a computer help desk for personal computer diagnostic and repair assistance.

- CU Woodshop Supply Inc. With a team made up of former contractors, experts woodworkers, and industry trainers, this project can help you with woodworking projects and questions. They have a consignment project to distribute used machinery, host an annual Used Tool Sale and Swap, and offer classes to help you learn woodworking skills that might assist with repairs as well as creative projects.

Wherever you live, you can watch for repair-related courses from local community colleges and park districts, and check to see if your local library operates a tool library, or at least lends some tools (e.g. you can check out a sewing machine and accessories from the Urbana Free Library). Many libraries also provide access to online research tools that can assist with auto and home repairs or more (e.g. see https://champaign.org/library-resources/research-learning).

Interested in starting your own repair-oriented project? Check out these additional examples and resources:

- Repair Cafés. You can also readan IGG blog post about this global phenomenon, and see the slides from a NYS DEC webinar on these types of projects in that state.

- Fixit Clinic. A particularly successful example exists in Hennepin County in Minnesota.

- Restart Project. Focused on electronics, this is a UK project, but you can host a “restart party” anywhere, and some K-12 schools, including some in the US are integrating restart centers to help teach repair skills and instill ideas of sustainability among students.

Learn more about the circular economy on the WRAP web site, or the Ellen MacArthur Foundation web site.